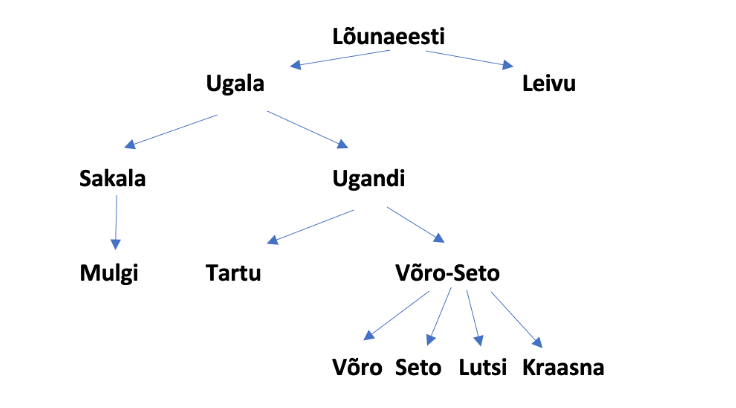

The prehistoric dialect of South Estonian was the first to diverge from the Finnic linguistic unity (viide). This divergence began during the Middle Proto-Finnic period more than 2000 years ago and was finalised during the Late Proto-Finnic period (fig. 1).

In the archaeological material, the difference of South Estonia (and North Latvia) from North Estonia becomes apparent during the Roman Iron Age, although the beginning of their divergence extends to the Pre-Roman Iron Age. This difference is an ancient cultural boundary across entire Estonia, that becomes traceable already during the Late Bronze Age. Whereas southern Estonia differentiated from the northern region by the scarcity of findings during the Pre-Roman Iron Age, during the Roman Iron Age different ceramics (so-called Late Textile Ceramics) and dissimilar ornaments stand out.

During the Roman Iron Age, more people arrived to South Estonia primarily from North Latvia, northern influences became weaker and later, and their extent was limited mostly to the northern part of South Estonia. To understand the peculiarity of the local language and culture, possible old (West Uralic) substrates must also be taken into account. With regard to the newcomers from North Latvia, they were probably also speakers of a South Estonian-type language, the mixture of their dialect with other South Estonian dialects resulting in the ancient South Estonian tribal language. The South Estonian spoken in North Latvia preserved, however, some unique features that appear in the later dialect of the Leivu language island.

There are differences between South Estonian and the other Finnic languages on all levels of language, including both archaisms and innovations. The phonology of South Estonia is distinguished from all the other Finnic languages by, for example, the change *kt > tt (e.g. tetti 'was made', nätt 'seen', cf. North Estonian tehti, nähtud 'id.'); there are many unique affricates (e.g. pütśk 'cow parsley', köüdś 'rope', ütś 'one', cf. North Estonian putk, köis, üks 'id.'); as well as – in addition to the mid-central õ – the high central vowel appearing, for example, in some back-vowel words in place of the first syllable i (nyna 'nose', sysalik 'lizard', cf. North Estonian nina, sisalik 'id.'; sysar 'sister', cf. Finnish sisar 'id.'), etc. Characteristic of the South Estonian grammar are the two conjugation types (cf. küdsä 'bakes (transitive)' and küdsäs 'bakes (intransitive)' and in the case of nouns, the convergence of the essive and inessive cases (e.g. olõ tervehnä 'be healthy', oll´ noorõh 'was young/in youth'). There are many unique words in South Estonian that have cognates only in more eastern Uralic languages (e.g. pähn 'linden', mõskma 'to wash', tsura 'young man').