During the second half of the I millennium AD, regional cultural differences in Finnic areas of Estonia, Latvia and Finland began to deepen. Four regions stand out the clearest: North Estonia (with Central and West Estonia), South Estonia with eastern North Latvia, the Daugava river delta with northern Courland, and Southwest Finland (with the adjacent inland regions). Cultural differences are most clearly traceable in pottery, especially fine ware, somewhat less in the rest of the material culture. Such a geographic division fits well with the third stage of Late Proto-Finnic as proposed by linguists, that is, when the linguistic differences of North Finnic, Central Finnic, Livonian and South Estonian had developed.

Chronologically the differences began to form in the 7th-8th centuries, though they became larger and clearer only during the Viking Age, that is, the 9th-10th centuries.

The eastern and northern neighbours of the Finnic peoples at the time were other linguistic relatives of a West Uralic origin (Chuds, Saami, etc.), in the south, however, the Baltic peoples. During the Viking Age, both Scandinavian Vikings as well as colonisers of (East) Slavic origin appeared around the Gulf of Finland, Volkhov river and Lake Ilmen.

North Estonia (Iru)

After the cultural expansion originating from North Estonia during the Roman Iron Age expanded east, south, west and north and unified the cultural scene in a widespread area, the development of regional differences can be seen during the second half of the I millennium. One of these regions is North Estonia with Central Estonia, Northwest Estonia, and West Estonia with the archipelago, where the so-called Iru type pottery spread. Such pottery is known also from the Izhorian plateau and as import goods in many places, e.g. Rurikovo Gorodische in Novgorod, Staraya Ladoga, Birka, etc.

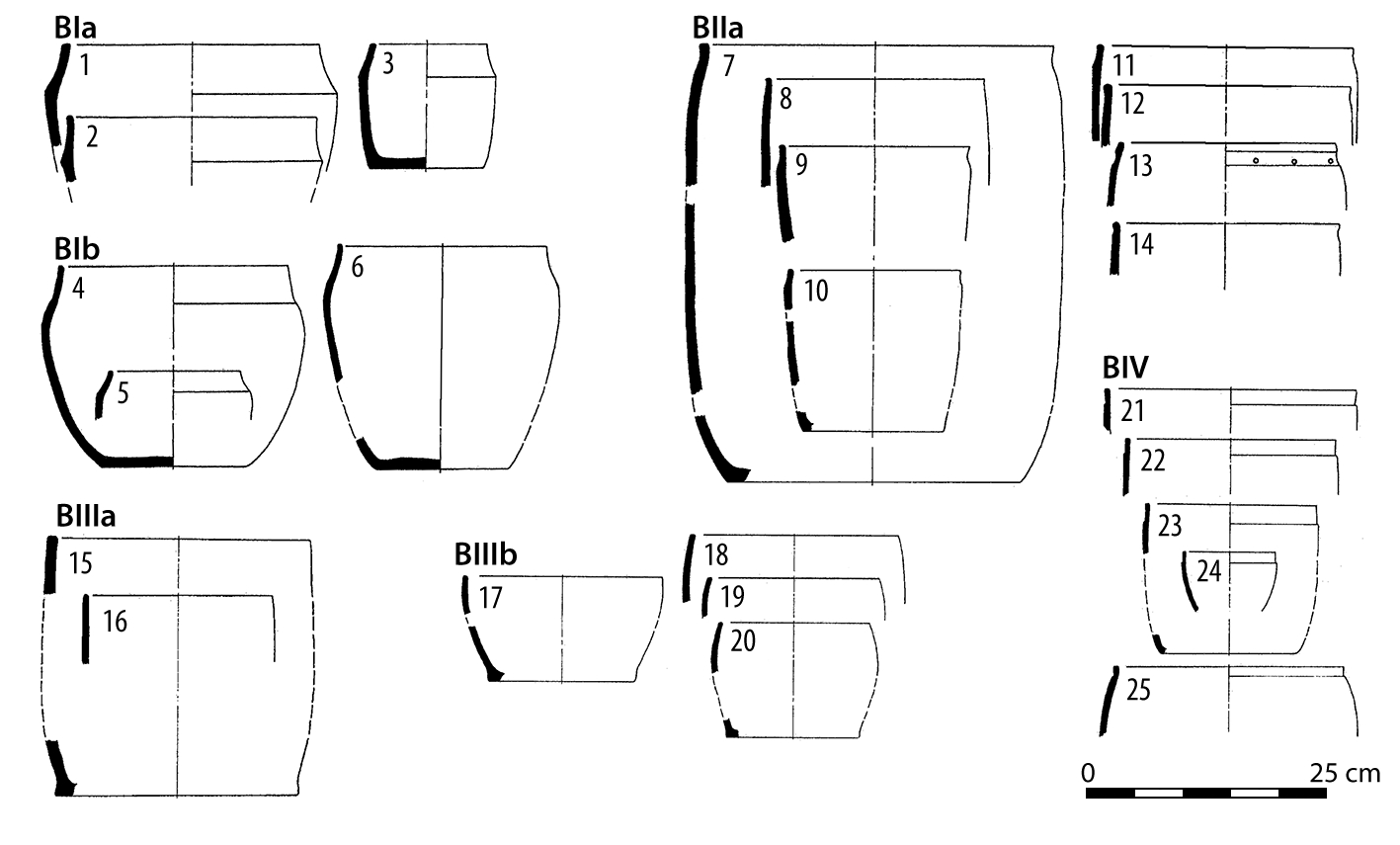

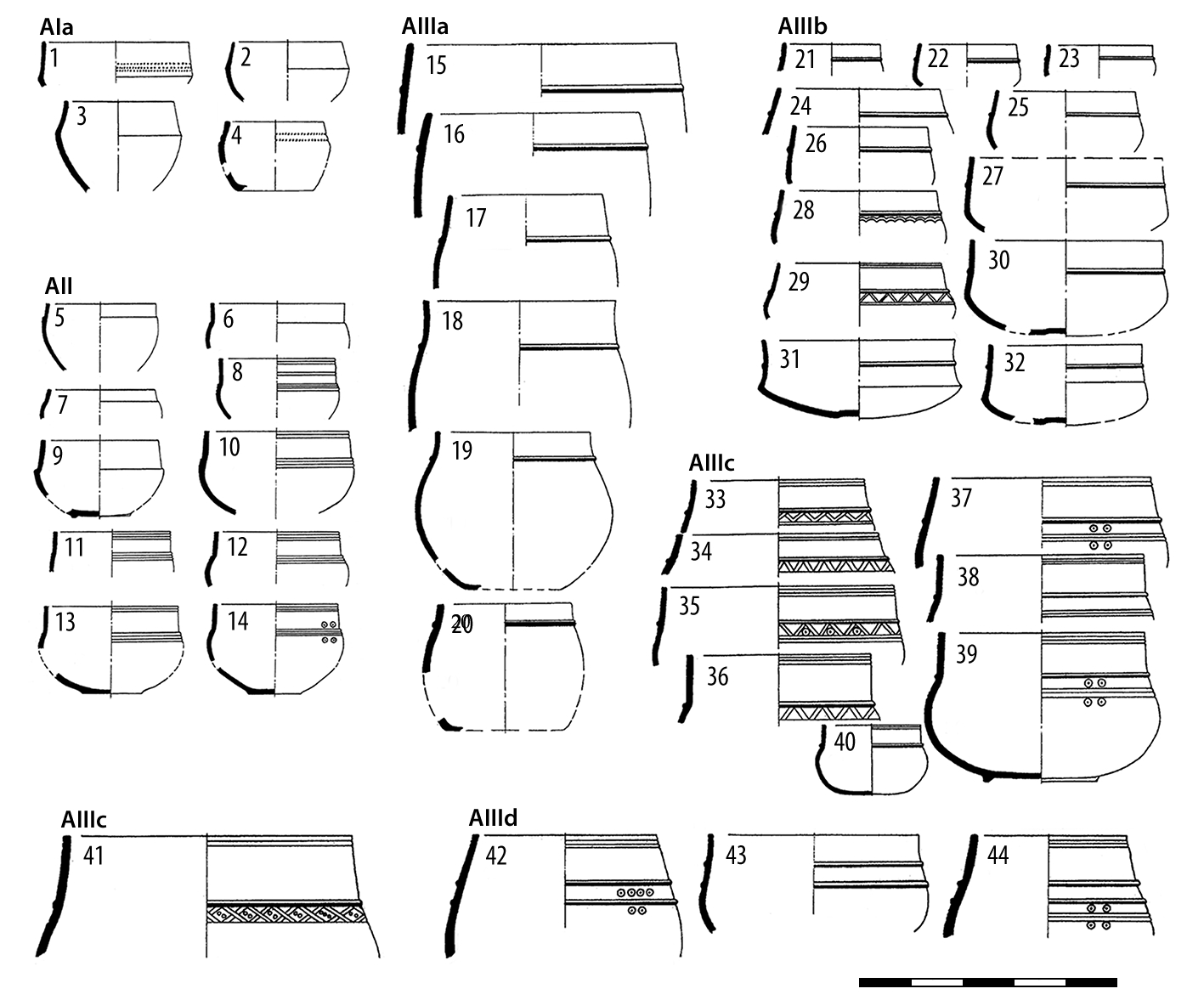

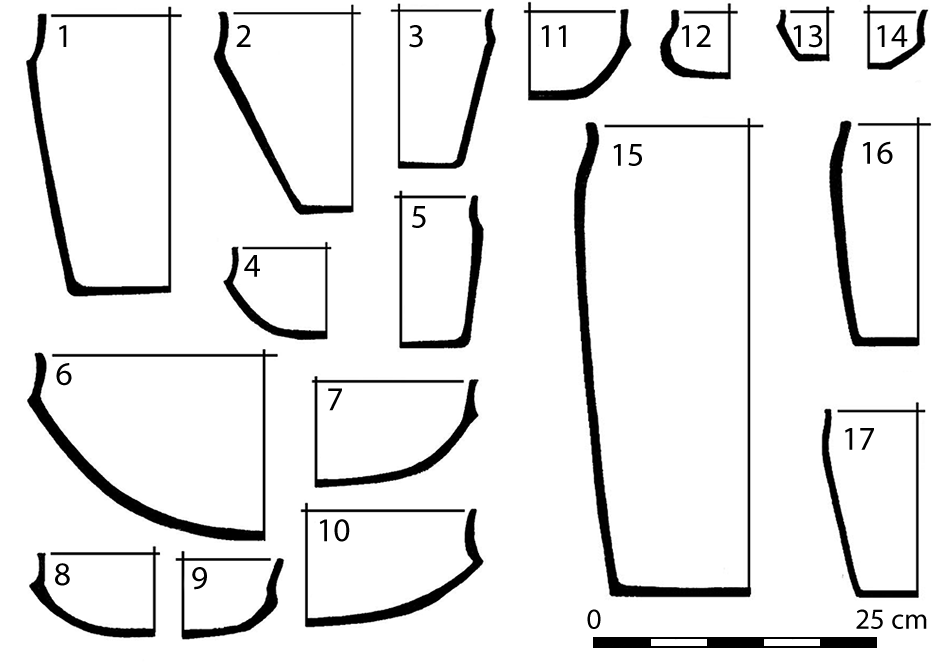

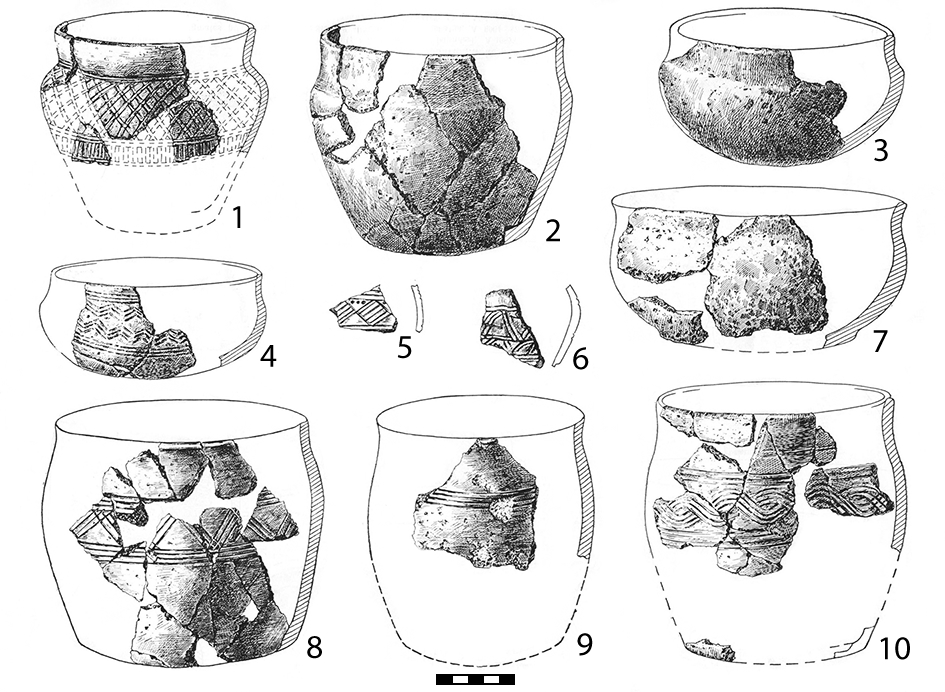

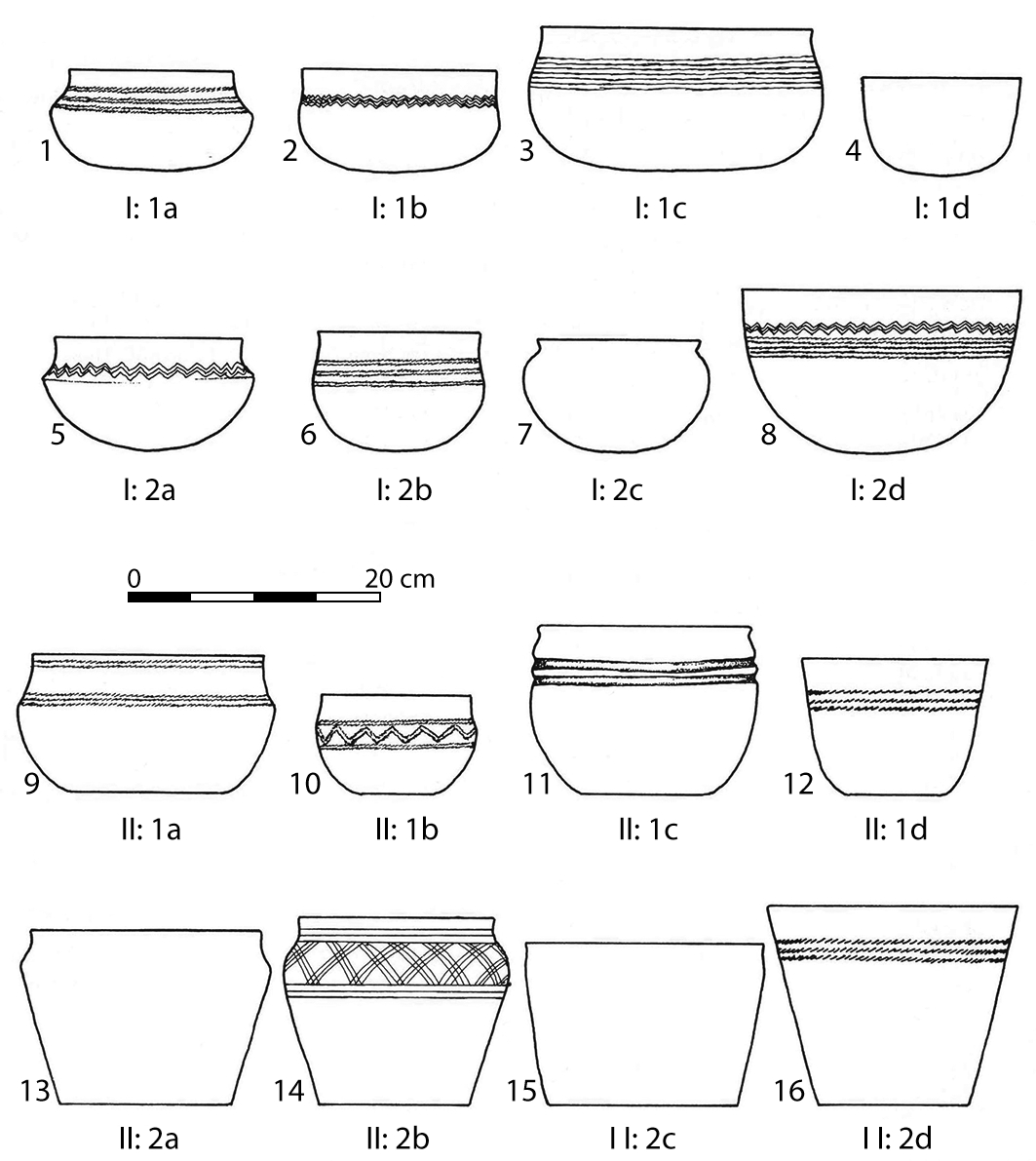

Two groups can be differentiated, coarse ware (Fig 1) and fine ware (Fig 2). Coarse ware is characterised by larger bucket-shaped or curve-shouldered household pots made with coarse-grained clay that is mostly undecorated. Fine ware is represented by many types of plates, bowls, but also relatively larger pots with a protruding body. The clay composition is fine-grained, carefully smoothed on the surface, at times even shining. Most of the fine ware pottery is elaborately decorated either with straight horizontal lines, zigzags or waves, eye stamp (point and circle) impressions, cord impressions, veins drawn with fingers or needle pricks.

Besides pottery, North, Central and West Estonia differ from their neighbouring regions also in other material culture, as well as their burial customs. These differences can be partly derived from a prior local basis, and partly from different external contacts that have taken place across the sea with Scandinavia and Finland and – especially concerning Saaremaa – with Courland.

Linguistically this cultural region can indicate the delineation of so-called Central Finnic, that is, North Estonian, against a Late Proto-Finnic background.

South Estonia (Rõuge)

Another essential region that can be distinguished based on archaeological materials in the second half of the I millennium is current South Estonia with its neighbouring regions in the south in North Latvia. The easternmost corner of Southeast Estonia remained out of this, where long barrows made from sand were widespread. The region in question differentiated already during the Early Iron Age, reflecting the divergence of the South Estonian language group from Proto-Finnic before the latter reached the level of Late Proto-Finnic.

The most characteristic element of material culture in the South Estonian region is the so-called Rõuge type pottery (Fig 3 and 4). As with other Finnic pottery, here too are two clearly distinguishable groups, coarse and fine ware. The prior is characterised by large bucket-shaped pots made from sand and stone clasts, the surfaces of which are crudely smoothed. A line of holes is often under the rim of the vessels.

The clay of the fine ware of the Rõuge type pottery is very fine, the surfaces of the vessels carefully smoothed and at times even burnished. There are low dish-shaped bowls and higher bucket-shaped pots, whereby in both cases the body runs with a carination over the neck that is turned inward. Ornamentation is not exactly frequent, composed usually of round-bottomed indentations that are aligned in rows or certain geometric patterns (e.g. triangles, squares, circles).

Whereas the extent of the eastern border of the Rõuge type coarse ware reaches rather far to the western part of Pskov region, fine ware, on the other hand did not reach further east beyond Võrumaa, that is, historical Setomaa; in the west it reached Viljandi. How far south did the border of Rõuge pottery reach, is not possible to determine more precisely due to the lack of corresponding specialised research. How the South Estonian cultural region was distinguished on the basis of other material culture in the second half of the I millennium is similarly difficult to determine, since relevant cemeteries are either unknown altogether or they are not studied. At the same time, the lack of known cemeteries can also be regarded as a cultural particularity – presumably the deceased were buried somehow differently than to their north or east.

Livonia and Courland (Daugmale)

With regard to historical linguistics, it isn’t quite clear when Livonian, that is, Gulf of Riga Finnic began to diverge from Late Proto-Finnic, although it likely occurred soon after the divergence of South Estonian. In the archaeological materials, this divergence is not visible before the final quarter of the I millennium, when a specific type of pottery started to spread along the lower course of Daugava river and to some extent also in North Courland; later also other distinguishing cultural elements arose. We can call this pottery type the Daugmale type (Fig 5) after its most significant findspot in the territory of the Daugava Livonians.

Among this high-quality fine ware, there are both low dish-shaped vessels as well as higher flat-based pots with an S-shaped profile. Both types of vessels are decorated with engraved line ornaments. The most widespread ornamentation motives are parallel horizontal lines, zigzag belts of multiple lines (usually between the horizontal lines), wave lines or plaits of wave lines between horizontal lines, needle pricks with zigzags, etc. The details of ornamentation and part of the motives, as well as the shape of the lower bowls very much resembles the Iru type fine ware, although the higher pots are of a rather original appearance, which has certain semblances of pots more of the Vanhalinna type of Southwest Finland.

Judging from the occurrence of burial forms characteristic of both Finnic and Baltic tribes, it is presumed that in the Gauja river region and lower course of Daugava river both ethnic groups lived together intermingled. Also at the end of the prehistoric era a clearly definable border was lacking between the Livonians and Latgalians. A more clearly defined and identifiable Livonian material culture becomes apparent from the 10th century onwards, when in addition to Daugmale pottery, a particular and unique female adornment complex appeared in wider use. This developed as the result of cultural influences received from many directions (especially Scandinavia and Finland). Surely people arrived at the lower course of Daugava river also from elsewhere in the beginning of the II millennium, although the demographic and cultural development in this region originated nevertheless from a local basis.

Also in North Courland, the earlier inhabitation of Finnic origin step by step intermingled with the Baltic, more specifically Curonian tribes, so that written sources from the beginning of the 13th century do not distinguish between these ethnic groups in any way. The Courland Finnic peoples did not develop a distinctive material culture comparable to that of the Gauja and Daugava Livonians, although they had many commonalities, including pottery. The Talsi castle became the most important centre for the Curonians along with its surrounding large settlement.

Southwest Finland (Vanhalinna)

The divergence of Finnish from the Late Proto-Finnic root is considered the third divergence of this proto-language, after South Estonian and Livonian had already diverged. Later the Karelian-Veps proto-language developed from the basis of Finnish.

Thanks to the geographic separation from the Late Proto-Finnic spoken in North Estonia beginning already during the Roman Iron Age, differences in material culture formed north of the Gulf of Finland even earlier and clearer than in the Livonian cultural region around the Gulf of Riga. Thus, already during the Migration Period, some types of artefacts originating from the Baltic region began to be manufactured somewhat differently and in the 7th-8th centuries an entire array of types of ornaments and weapons characteristic of Southwest Finland were created: crayfish fibulae, symmetric fibulae, azure disc-shaped plate fibulae, wide-ended hollow-convex bracelets, certain spearhead and battle knife types, etc. Also fine ware developed distinctively, while coarse ware retained similar forms to those of North Estonia for a long time. In addition, part of the other material culture, as well as low flat-cairn cremation cemeteries remained similar on both sides of the Gulf of Finland.

A good overview of Pre-Viking Age and Viking Age pottery in Southwest Finland is revealed by both cemeteries as well as some archaeologically studied settlements and forts; among the latter of which the most significant is Vanhalinna near Lieto. The clay mass and surface processing of the local pottery is very similar to Iru fine ware, although differences are apparent in the shape and especially the ornamentation of the vessels. In Vanhalinna type pottery, there are more curved-shouldered and -bottomed bowls, both lower and higher ones. Ornamentation elements are the same as in North Estonia, although their placement and combinations are largely different. A special popularity in the pottery of Southwest Finland was won by wave lines, cord ornamentation and parallel veins pulled with fingers.

We can thus observe the deepening of cultural differences on the two sides of the Gulf of Finland throughout the entire second half of the I millennium and naturally also later, although many characteristics still remained to unite the neighbouring tribes. Surely also differences of the Finnish and North Estonian languages developed and deepened corresponding to the divergence of cultures and the reduction in mutual interaction.

Eastern and northern neighbours of the Finnic peoples

During the second half of the I millennium, the extensive regions to the east and north of the Finnic peoples were inhabited by tribes who spoke related languages that descended from the onetime West Uralic proto-language. The ancestors of these peoples also had departed from Volga-Oka-Kama region to the west and northwest already during the Bronze Age or Early Iron Age, although they remained mostly to inhabit regions east of Lake Peipsi and reaching Karelia and Finland. Who these tribes were and how many were they is not possible to know certainly, because they were mostly assimilated to the later Finnic and East Slavic peoples. Only some names have reached us in Old Russian chronicles, such as Chuds, Meryans, Muromians, Meschera, etc. The only people remaining are the Saami who reached Fennoscandia.

In the beginning, that is, during the Bronze Age and Pre-Roman Iron Age, it was the Saami who populated almost the entirety of Finland, there was less of them only on the coastal zone. Finnic groups arriving from the south have thereafter continually pushed the Saami linguistic and cultural area to the north. Since the current Finns are genetically more similar to the Saami than the Estonians, the mentioned Finnic advance took place atleast partly through the language shift and cultural adaptation of the Saami. The first Finnic peoples from Southwest Finland among the indigenous West Uralic (Saami) people of the Karelian isthmus arrived only in the 7th-8th centuries. Later their influence became stronger, bringing along the Finnicisation of the entire isthmus, the southern and eastern shores of Lake Ladoga and the eastern part of the Izhorian plateau. The western part of the Izhorian plateau was Finnicised via the migrants arriving from North Estonia.

In the eastern part of Southeast Estonia and in regions to its east, the burial tradition of so-called long barrows was born in the middle of the I millennium. The population building and being buried in these has been considered as either East Slavic or so-called eastern Finnic, although in essence it was a people of West Uralic origin that is not correct to be called Finnic (their language did not take part in the characteristic developments and contacts of Finnic). As a people, they could have received the name Chud from the onslaught of the Eastern Slavs. By the beginning of the II millennium they were Slavicised, as were also other peoples descending from a West Uralic origin to the east of Lake Peipsi during the following centuries. The genetic similarity of the West and Northwest Russians with Finnic peoples indeed does point to such a process of assimilation.